The Bröhan-Museum

Project partner of Philipps-Universität Marburg (UNIMAR)

![]()

The Bröhan-Museum specializes in Art Nouveau, Art Deco and Functionalism of international provenance. The collection has two areas of primary interest: decorative arts and painting. The art objects are arranged in room ensembles for presentation. These ensembles aim at giving a representative synopsis of the period from Art Nouveau - as a precursor of modern design - up to Art Deco and Functionalism by way of chosen pieces of glass, ceramics, porcelain, silver and metal work in combination with furniture, carpets and lighting as well as prints and painting. The collection illustrates the equal value of each area of artistic production.

The Bröhan-Museum specializes in Art Nouveau, Art Deco and Functionalism of international provenance. The collection has two areas of primary interest: decorative arts and painting. The art objects are arranged in room ensembles for presentation. These ensembles aim at giving a representative synopsis of the period from Art Nouveau - as a precursor of modern design - up to Art Deco and Functionalism by way of chosen pieces of glass, ceramics, porcelain, silver and metal work in combination with furniture, carpets and lighting as well as prints and painting. The collection illustrates the equal value of each area of artistic production.

It gives priority to works of French and Belgian as well as of German and Scandinavian Art Nouveau besides ensembles of French Art Deco. The Bröhan-Museum houses an exceptionally rich collection of porcelain from distinguished manufactures (KPM Berlin, Royal Copenhagen, Meißen, Nymphenburg, Sèvres etc.) as well as pieces of metal work from the most important artists and designers of the time including early industrial design.

The Bröhan-Museum is named by its founder, Karl H. Bröhan, who donated his private collection to the city of Berlin on occasion of his 60th birthday. From 1966 onwards, he continuously built up his collection and made it public in a villa in Dahlem since 1973. On October 14th, 1983, the collection moved to its present site, a late classicistic barracks within the Charlottenburg palace ensemble. 1994, the Bröhan-Museum became a state museum.

The spectre of the Bröhan collection includes prominent examples from the work of the following artists and producers: Precious glass by Emile Gallé and Joh. Loetz Wwe., furniture by Peter Behrens, Eugène Gaillard, Hector Guimard, Louis Majorelle, Joseph Maria Olbrich, Bruno Paul, Richard Riemerschmid, examples of Art Deco in the metal works of Edgar Brandt, furniture ensembles by Jacques-Emile Ruhlmann, silver by Jean Puiforcat, Paris, and Georg Jensen, Copenhagen, as well as Art Nouveau fayence from the Bohemian Amphora works. One of the cabinets is dedicated to the Belgian Art Nouveau artist Henry van de Velde and another to the Vienna Secession artist Josef Hoffmann.

Featured Artists:

Emile Gallé (1846–1904): Like many of his contemporaries, Nancy-based Emile Gallé was an enthusiastic disciple of East Asian art. Of particular importance for him was his friendship with the Japanese natural scientist and draughtsman Tokouso Takashima, who was in Nancy from 1885 to 1888 for study purposes. Gallé developed a glass style of his own known as the Gallé genre, which drew on many different influences and indeed became emblematic of Art Nouveau in Lorraine. It combined decoration and technology, nature motifs and colour effects in a way that was new to the art fashion of the time. All symmetry and regularity was dispensed with. Gallé’s view of nature was strongly coloured by his interest in botany. He sought to capture mood, using the play of colour and light that only glass could offer. A particular colour effect is achieved in this vase through the metal foil overlaid with green glass.

Emile Gallé (1846–1904): Like many of his contemporaries, Nancy-based Emile Gallé was an enthusiastic disciple of East Asian art. Of particular importance for him was his friendship with the Japanese natural scientist and draughtsman Tokouso Takashima, who was in Nancy from 1885 to 1888 for study purposes. Gallé developed a glass style of his own known as the Gallé genre, which drew on many different influences and indeed became emblematic of Art Nouveau in Lorraine. It combined decoration and technology, nature motifs and colour effects in a way that was new to the art fashion of the time. All symmetry and regularity was dispensed with. Gallé’s view of nature was strongly coloured by his interest in botany. He sought to capture mood, using the play of colour and light that only glass could offer. A particular colour effect is achieved in this vase through the metal foil overlaid with green glass.

Hector Guimard (1867–1942) is considered one of the major architects and all-round designers of French Art Nouveau. Influenced by the filigree patterns of Gothic art, which became popular towards the end of the 19th century thanks to Viollet-le-Duc and the enthusiasm for nature of early Art Nouveau, which sought inspiration in the structure of plants, he designed extravagantly curvaceous flower sculptures that are still a prominent feature of the urban landscape of Paris. He it was who designed the cast-iron entrances to the first metro stations in time for the world exhibition in 1900. The buffet with the water lily leaves and stems was designed for the Castel Henriette villa in Sèvres. The dynamic language of natural shapes is again the model for Guimard here. The plant patterns develop out of the body of the buffet in vertical, organic curves. This asymmetrically designed piece of furniture almost seems like a plant sculpture. The choice of cherry wood, too, sets it wholly apart from the heavy, imitative furniture styles of historicism.

Hector Guimard (1867–1942) is considered one of the major architects and all-round designers of French Art Nouveau. Influenced by the filigree patterns of Gothic art, which became popular towards the end of the 19th century thanks to Viollet-le-Duc and the enthusiasm for nature of early Art Nouveau, which sought inspiration in the structure of plants, he designed extravagantly curvaceous flower sculptures that are still a prominent feature of the urban landscape of Paris. He it was who designed the cast-iron entrances to the first metro stations in time for the world exhibition in 1900. The buffet with the water lily leaves and stems was designed for the Castel Henriette villa in Sèvres. The dynamic language of natural shapes is again the model for Guimard here. The plant patterns develop out of the body of the buffet in vertical, organic curves. This asymmetrically designed piece of furniture almost seems like a plant sculpture. The choice of cherry wood, too, sets it wholly apart from the heavy, imitative furniture styles of historicism.

The restless linearity also extends to the darting details of the appliqué work—a seismic expression of artistic sensibility and restlessness around the turn of the century.

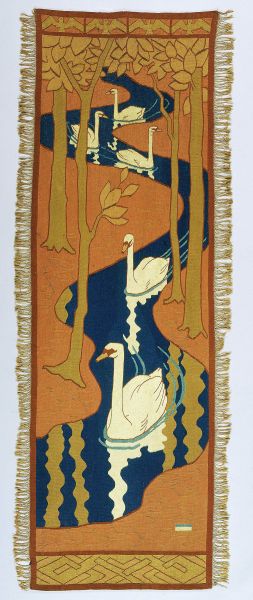

Otto Eckmann (1865–1902): The art weavers’ college at Scherrebek (now Skærbæk, Denmark) was founded in 1896 in the wake of the fin-de-siècle art reform movement. Particularly in the countries of northern Europe, there was a new enthusiasm for textile art. Tapestries reached high artistic standards and became outstandingly important as an integral component of interior design. Around 1894, Otto Eckmann, who was originally a painter, resolutely put down his brushes in favour of applied art—a decision that was taken by numerous artists of the generation around 1900. The aesthetic design of the totality of solid objects proved to have greater appeal than the specialised field of painting. Eckmann became famous as a designer not only of book art and typography, but also of furniture and metal items. The Swans tapestry one of the most successful designs of the weaving college at Scherrebek—combines modern design principles with East Asian influences, a combination that would prove to be one of the principal artistic currents of the Art Nouveau movement. Abstraction, stylisation and aesthetic priorities were borrowed from Japanese art. In this case, Eckmann even went so far as to adapt the tall, narrow format of a Japanese kakemono (roll picture).

Per Algot Eriksson (1868 – 1937): Sweden played a considerable part in the international artistic debate associated with the reform movement around 1900, thanks to the output of the Rörstrand porcelain factory in Stockholm. The factory’s artistic director was the painter and versatile handicrafts designer Alf Wallander (1862–1914). Under his artistic aegis, he developed a special style of porcelain that was shown at the major exhibitions of the day–particularly in Germany—to great acclaim. A characteristic of the new porcelain creations was the rendering of plant decoration in relief or the three-dimensional form of flowers and plants. The delicate coloration of the blue and green tones gives these one-off pieces an especially delicate and decorative look. The large baluster pot is a graceful representation of an underwater world. The large, open bloom of the water lily is developed in three dimensions, like the typical leaves and buds resting on the shoulder of the vase, while the roots and stems that reach down into the depths of the water are shaped in light relief in the delicate range of blue tones of the water.

Per Algot Eriksson (1868 – 1937): Sweden played a considerable part in the international artistic debate associated with the reform movement around 1900, thanks to the output of the Rörstrand porcelain factory in Stockholm. The factory’s artistic director was the painter and versatile handicrafts designer Alf Wallander (1862–1914). Under his artistic aegis, he developed a special style of porcelain that was shown at the major exhibitions of the day–particularly in Germany—to great acclaim. A characteristic of the new porcelain creations was the rendering of plant decoration in relief or the three-dimensional form of flowers and plants. The delicate coloration of the blue and green tones gives these one-off pieces an especially delicate and decorative look. The large baluster pot is a graceful representation of an underwater world. The large, open bloom of the water lily is developed in three dimensions, like the typical leaves and buds resting on the shoulder of the vase, while the roots and stems that reach down into the depths of the water are shaped in light relief in the delicate range of blue tones of the water.

Images, Bröhan-Museum, Berlin

1. Vase with moth

Emile Gallé, Nancy, c.1898

Flashed glass with fusions and metal foil inclusions, cut

Height 18.5 cm; inv. no. 75-013

2. Buffet

Hector Guimard , 1899/1900

Cherry wood with brass fittings and glass

Height 274 cm; inv. no. 83-001

3. Five Swans tapestry

Otto Eckmann, 1896/97

Kunstwebschule Scherrebek

Wool, tapestry weave

Length 235 cm, width 75 cm; inv. no. 93-911

4. Centrepiece with water lilies

Per Algot Eriksson, c.1900

Rörstrand’s Porslinsfabriker AB, Stockholm

Porcelain with underglaze painting

Height 29 cm; inv. no. 92-045